By Maanasa Kona and Sabrina Corlette

Employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) provides critical coverage for 160 million Americans. However, the adequacy of these plans is in decline, leaving many workers and their families underinsured. Employers acting alone will not be able to reverse this decline. Policy change is needed, but assessing what policies will work, and be feasible, is challenging. In this new series for CHIRblog, we assess some proposed policy options designed to improve the affordability of ESI, the state of the evidence supporting the proposed policy change, and opportunities for adoption. In this, the first of the series, we review the primary drivers of the erosion occurring in ESI and identify three recognized policy options to improve affordability for employers and workers alike. Following blogs will dive deeper into each of the potential policies.

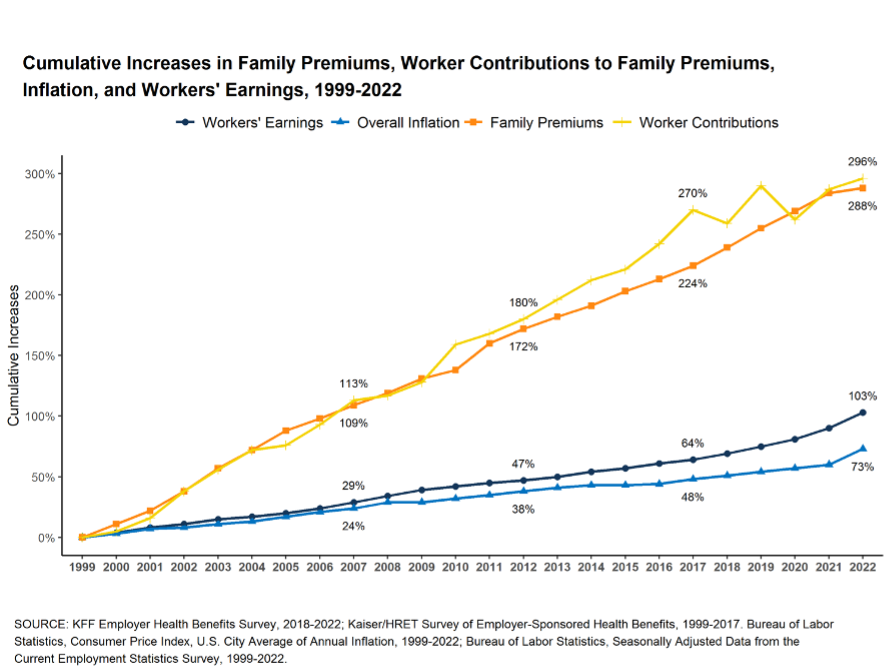

In 2021, about 160 million Americans, approximately half of the country, received health insurance through their employers, making employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) the single largest source of insurance in this country. America is the only developed nation that relies so heavily on employers for health insurance coverage, and over the last couple of decades, the generosity or comprehensiveness of ESI has been in steady decline, leaving more and more working adults in the country underinsured. A recent Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that employee premium contributions have risen by about 300% since 1999, and the average deductible for a single worker increased from $303 in 2006 to $1,562 in 2022. Today, about a third of working adults covered through ESI face an annual deductible of about $2000 or more. See Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Rising premiums as well as rising out-of-pocket costs like deductibles have left American workers financially exposed. A recent survey by the Commonwealth Fund found that about a third (29%) of working adults covered through ESI are currently enrolled in plans that offer inadequate coverage. This means that though they were covered by health insurance all year round: (1) their out-of-pocket costs, excluding premium contributions, were 10% or more of their household income (5% or more for those under 200% of the federal poverty level); or (2) their deductible constituted 5% or more of their household income. Further, this burden is not borne equitably by all working adults covered through ESI. Lower-income families and families with sick family members end up spending a greater portion of their income on both premium contributions and out-of-pocket health care costs.

It has long been accepted that the biggest contributor to rising premiums and deductibles is rising health care prices, specifically hospital prices, but historically, employers have mostly sought to combat this problem by shifting the financial burden towards employees and trying to limit how much they use health care services. These strategies have only served to erode the financial security of employees while doing very little to tackle the real problem—the high and constantly rising prices of provider services and prescription drugs.

In addition to increasing the financial burden on working adults, rising health care prices can also throttle the growth of business and contribute to inflation. A recent survey found that a majority of small business leaders cite health care costs as their most important business challenge, with about 41% delaying growth opportunities and 37% increasing the prices of their goods and services because of health care costs.

Can Employers Do Anything About Increasing Health Care Prices?

The short answer is: not without significant help from the government, both federal and state.

A recent Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report finds that rising health care prices are mostly driven by outsized hospital and physician market power combined with a lack of price sensitivity on the part of employers who buy these services. Employers have generally relied on third-party administrators (TPAs) or middle men, like health plans and pharmacy benefit managers, to manage day-to-day operations and contracts with providers. These TPAs often have misaligned incentives – benefiting from increased revenue when provider prices go up, and passing along those price increases to employers and their employees in the form of higher premiums and/or cost-sharing. However, the recently enacted federal Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA) has put employers on notice: as health plan fiduciaries, it is their responsibility to oversee the TPAs they contract with and to pay only “reasonable fees” for services provided to the plan.

Some employers have already taken on a more active role in acquiring affordable health care services for their employees. Some directly negotiate rates with providers while others directly provide services to their employees. Some employers have banded together to gain more negotiating power as a purchasing collective. For example, the Peak Health Alliance was established in Summit County, Colorado to bring together public and private employers as well as individuals who buy insurance on the marketplace to negotiate prices as a group. Peak Health has been able to negotiate a fee schedule for many procedures with one health system, which resulted in significant cost savings. Recently, Peak Health Alliance expanded to three additional counties.

In Indiana, the Employers’ Forum, a coalition of 154 self-insured employers, partnered with the RAND corporation to study hospital prices in the state. When reports released in 2019 and 2020 found that Indiana had some of the most expensive hospital prices in the nation, employers began exerting pressure on their TPAs to negotiate better deals, and they have seem to have been successful with respect to at least one TPA and its contract with a dominant hospital system.

However, such alliances are hard to replicate on any broad scale. Most employers lack sufficient data – and internal data analytic capacity – to assess health care prices. Further, the extensive hospital and physician consolidation in many markets makes it challenging for employer coalitions to gain meaningful price concessions

How Can Federal and State Action Help Drive Down Health Care Prices?

Two recent reports, the CBO report mentioned above and a Bipartisan Policy Center report assess several federal and/or state level policy interventions that can exert a downward pressure on commercial market health care prices. The types of interventions discussed in these reports include:

- Directly or Indirectly Regulating Health Care Prices. CBO finds that direct government regulation of provider prices is likely to have the most impact on affordability. Such regulation can include direct measures like capping prices, capping the growth of prices, or capping the growth of premiums. They can also include more indirect measures like developing state-level cost containment commissions and strengthening state rate review processes.

- Reducing Consolidation and Anti-Competitive Behavior. CBO finds that more robust anti-trust regulation and enforcement can have a modest impact on health care prices. The BPC report and a subsequent panel discussing the report proposed strengthening antitrust enforcement at the federal level for large-scale mergers and also at the state level for smaller mergers with greater local impact. Other policy options include prohibiting anti-competitive contracting practices as well as promoting market entry and competition.The Biden administration has begun taking a closer look at enhancing antitrust enforcement, and bipartisan legislation in Congress would limit the anti-competitive practices of monopolistic provider systems.

- Improving Price Transparency. CBO finds that improving the transparency of the prices employers pay for health care goods and services, by itself, is likely to have a very small impact on price inflation, but it can serve as a catalyst for more significant action by both employers and policymakers. The federal government recently enacted regulations requiring both hospitals and health insurers to make their negotiated prices public, but the compliance with these requirements has been spotty.

Looking Forward

About half of Americans are covered by employer-provided health insurance plans, but the adequacy of these plans has been eroding over time. This has left many low-income workers facing significant financial burden despite being enrolled in what has generally been considered the “gold standard” of U.S. health insurance coverage. High and rising health care prices are the primary contributor to this problem, but employers are ill-equipped to curb health care prices by themselves. Federal and state policymakers have several options at their disposal to control and reduce health care prices and alleviate the burden on many low-income working Americans. The next three blogs in this series will take a deeper look at the three policy options discussed above.

2 Trackbacks and Pingbacks