“Have you heard about this new health care sharing insurance?”

Someone asked me this question on a recent flight, and, while I am usually not real chatty on 6am flights, I made an exception for this particular issue. Health Care Sharing Ministries (HCSMs) are not new, and they are not insurance. According to the Alliance of Health Care Sharing Ministries, HCSMs have over 160,000 members in all 50 states, and a growing number of states have said in state law that HCSMs are not insurance. Further, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) exempts members of HCSMs from the personal responsibility requirement if the HCSM meets the criteria listed in the ACA (in particular, the organization must be a 501(c)(3) organization, must have been in existence since Dec. 31, 1999, and must conduct an annual audit that is made available to the public upon request).

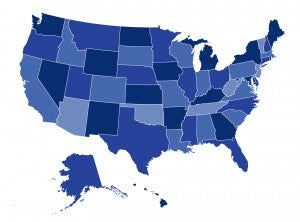

Where does my state fit in?

Twenty-one states have laws saying health care sharing ministries are not insurance:

- Alabama

- Arizona

- Florida

- Georgia

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Maine

- Maryland

- Michigan

- Missouri

- New Hampshire

- North Carolina

- Oklahoma

- Pennsylvania

- South Dakota

- Utah

- Virginia

- Washington

- Wisconsin

A twenty-second state, Massachusetts, exempts members of HCSMs from joining the state’s health insurance exchange marketplace (called the Connector).

Legislative tracking by CHIR faculty suggests that states will continue to consider HCSM legislation during their 2013 legislative sessions.

How does it work?

Members of HCSMs pay a monthly “share” based on their participation level and those shares are matched with another member’s eligible medical bills. Names and current needs of members are published in a monthly newsletter, and members are able to support each other both financially and through prayer.

This seems reasonable. So why did this topic make me so chatty all of a sudden? As it turns out, HCSMs could be a nightmare for some consumers since state protections do not apply to this type of arrangement.

First, HCSMs use concepts that look a whole lot like insurance. Members must pay their monthly share in order to maintain membership (the insurance industry calls it a ‘premium’). Members have to meet an ‘initial member responsibility’ amount (a.k.a. the ‘deductible’ in the insurance world). As documented in Bowman v. Medi-Share, the HCSM in question took a certain amount out of each monthly payment to cover expenses and salaries of officers and employees (insurance wonks are thinking “MLR” right now) and also had annual and lifetime limits, provider networks, and underwriting manual.

Second, if HCSMs are not insurance, they are not subject to reserve requirements. While an insurance company can’t get licensed to do business in a state without significant reserves for cases of insolvency, HCSMs have no such requirement. If the HCSM does not receive enough monthly share contributions to cover eligible medical expenses and the HCSM goes under, then the members just don’t get their medical bills paid.

Third, if a member doesn’t get medical bills paid or has a problem with the HCSM, state insurance regulators don’t have jurisdiction to help the HCSM member because state insurance laws do not apply. The member’s remedy would be through the attorney general’s office and/or the courts (an expensive and lengthy process in most cases).

The courts are divided in their opinions of HCSMs. The Iowa Supreme Court held in 1999 that an HCSM did not constitute insurance (Barberton Rescue Mission, Inc. v. Insurance Division of the Iowa Department of Commerce, 568 N.W. 2d 352). On the other hand, the Supreme Court of Kentucky held in 2010 that an HCSM was insurance (Kentucky v. Reinhold, 325 S.W. 3d 272). Both courts examined whether or not risk of payment of medical expense is assumed by the HCSM. In Iowa, the court found that the HCSM did not assume risk because the medical needs of members are paid by other members. In Kentucky, the court found that because members must pay their share to remain eligible to receive payment for their own medical expenses, the risk clearly shifted to the HCSM.

It may come as a shock to some members that HCSMs can, in fact, refuse to cover certain claims arising from “un-Christian” behavior, and still impose lifetime and annual limits. While these practices are prohibited under the Affordable Care Act, such protections do not apply to HCSMs. In addition, starting in 2014, insurance consumers who purchase insurance in the Health Insurance Marketplace may be eligible for subsidies and tax credits – opportunities not available to members of HCSMs.

It’s not that these arrangements are inherently bad. It’s that they avoid being subject to the consumer protections available to those individuals who are covered by products sold in the insurance market. As I told my seat mate on that early morning flight, when I was feeling so chatty: do your homework and decide what trade-offs you’re willing to make.

Stay tuned to CHIRblog for more updates on health insurance issues you need to know about in our “State of the States” series!