By Sabrina Corlette, Rachel Swindle, and Rachel Schwab

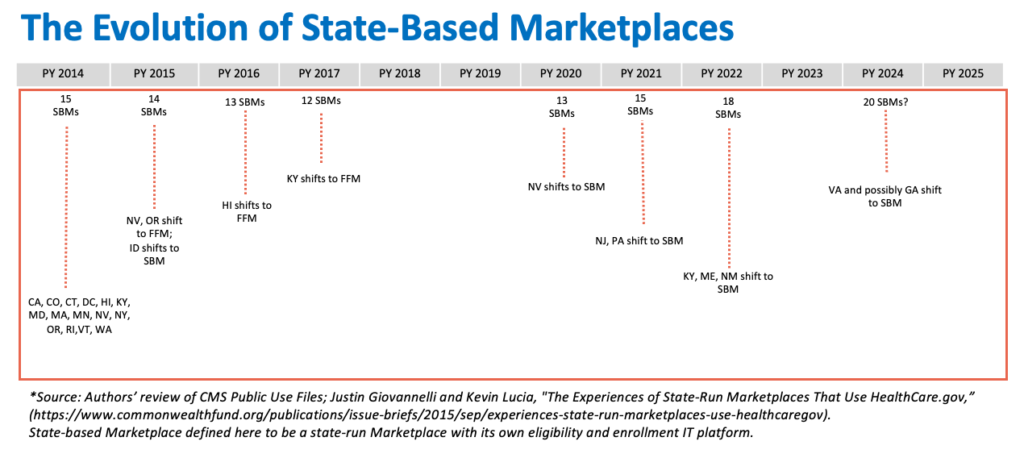

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) established health insurance Marketplaces (or “Exchanges”) to facilitate enrollment in comprehensive and affordable health insurance plans. The ACA envisioned that the Marketplaces would be primarily state-run, with the federal government stepping in as a backstop. In practice, due in part to deep anti-ACA sentiment among some state policymakers, when the Marketplaces launched in 2013, only 14 states and the District of Columbia were state-run Marketplaces with their own IT eligibility and enrollment platforms.* The federal government had to run the Marketplaces in the remaining 36 states, and since the inaugural year, some state-run Marketplaces have used the federal enrollment platform HealthCare.gov. Over the course of the first decade of the ACA’s Marketplaces, the number of state-based Marketplaces (SBM) has fluctuated from 15 in the first year, to a low of 12 in plan year 2017, to the current 18 in 2023. (See Exhibit). States transitioning to a full SBM in recent years sought control in part because the Trump administration’s efforts to roll back the ACA led to instability in their insurance markets and an increase in the numbers of uninsured. The ability to adapt an SBM to state circumstances and priorities has enabled these states to build on the ACA and expand enrollment.

More recently, several additional states have indicated they may undertake a transition to an SBM, including Georgia and Texas, where opposition to the ACA remains a bedrock principle for many lawmakers. With overall Marketplace enrollment at an all-time high, and millions more people poised to transition from Medicaid to commercial insurance, the role of the ACA’s Marketplaces as a health coverage safety net has never been more pivotal. Yet federal rules implementing the ACA impose few standards for launching and maintaining a Marketplace that adequately serves consumers and builds on enrollment gains. Given states’ interest in taking over operation of the Marketplaces, it may be time for the federal government to establish a stronger federal floor.

The Need For Minimum Standards Before Operating a State-based Marketplace

To date, SBMs have been leading the way towards greater insurance coverage and an improved consumer experience. They are investing heavily in marketing, outreach, and enrollment assistance, coordinating with Medicaid agencies to reduce churn, raising the bar on quality for participating insurers, and acting to improve the consumer shopping experience. Many SBMs have implemented innovative strategies to reach the remaining uninsured, such as state-funded subsidies, coverage for undocumented residents, and “easy” or automatic enrollment.

In the last two years, the federally facilitated Marketplace (FFM) has been catching up. The FFM has dramatically increased funding for marketing and enrollment assistance. Federal officials have also implemented new policies to lengthen enrollment windows, simplify plan choices, expand eligibility for tax credits (by fixing the “family glitch”), and reduce the volume of paperwork for consumers to remove enrollment obstacles. These efforts are paying off, with record-breaking FFM enrollment in 2023.

Any state seeking to transition from HealthCare.gov to SBM status today thus has a higher risk of backsliding on these coverage gains. The ACA specified that state Marketplaces predating law’s enactment, such as Massachusetts’s Marketplace, were presumed to qualify under the new federal standards for SBMs only if they continued to cover approximately the same portion of the population projected to be covered nationally under the ACA. The assumption was that SBMs need to build on, not detract from, the ACA’s coverage goals.

Yet not all state leaders seeking to launch an SBM share a commitment to universal insurance coverage. Indeed, 10 states, including Georgia and Texas, have not taken up the option to expand Medicaid coverage to their poorest residents. And although states are generally the first line of enforcement of the ACA’s market reforms, Texas has declined to play this role, and instead relies on federal enforcement. Moreover, Georgia has previously sought permission to bypass several key Marketplace requirements, including the centralized enrollment website. Instead, the state proposed to send consumers to private insurers and brokers, both of which have financial incentives to limit meaningful plan comparison.

Marketplace Roles and Responsibilities

Under current federal rules, SBMs have a long list of critical responsibilities, but are subject to relatively minimal federal standards for how they perform these duties.

Governance

States can establish a Marketplace as a governmental agency or non-profit entity. Marketplaces run by independent state agencies and non-profit entities must have a governing board bound by a formal and public charter or by-laws, hold regular and open meetings announced in advance, and meet certain membership standards, such as a ceiling on members with ties to the health insurance industry. Marketplace boards must also have publicly available policies governing conflicts of interest and financial interest disclosures, ethics principles, and accountability and transparency standards. Federal rules implementing the ACA do not specify the number of times Marketplace boards must meet annually, how far in advance meetings must be announced, the number of individuals on the governing board, if there are term limits for voting board members, or how board members are selected or appointed.

Funding

In establishing a Marketplace, states must ensure it is financially self-sufficient. States have broad flexibility to choose the mechanism by which they fund their Marketplace, such as an assessment or fee on insurers or a state appropriation of other funds. States may also apply for future federal grants, such as when Congress allocated additional funding under the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA).

Stakeholder Consultation

The ACA requires Marketplaces to consult with stakeholders on a “regular and ongoing basis,” including Marketplace enrollees, individuals and entities facilitating Marketplace enrollments, small businesses representatives, the state’s Medicaid agency, “advocates for enrolling hard to reach populations,” federally recognized Tribes, public health experts, providers, large employers, insurers, and agents/brokers. Federal rules do not specify the frequency or form for stakeholder consultation, which components of the Marketplace operations are subject to stakeholder input, or a process to ensure stakeholder feedback is incorporated into Marketplace policies and practices.

More Than a Website

The Marketplaces must perform several functions designed to ensure that consumers are able to understand their options, determine their eligibility for premium tax credits, and enroll in a health plan that meets minimum standards. These functions include:

Plan Management. States that operate their own Marketplaces are responsible for certifying that health plans are “qualified health plans” (QHPs), products eligible to be sold on the Marketplace. This means the plans must meet federal and state benefit requirements, premium rating rules, prescribed “actuarial value” or plan generosity levels, prohibitions against discriminatory benefit design or pre-existing condition limitations, and network adequacy, among other standards. While some requirements apply to plans in every Marketplace, others, such as specific network adequacy standards, vary depending on whether the Marketplace is state- or federally run. Some Marketplaces that operate independently of their state department of insurance (DOI) still rely on their DOI for certain plan management tasks.

Online Eligibility and Enrollment Platform. Marketplaces must maintain a website for consumers to shop for and enroll in coverage in a way that is accessible for those with disabilities and/or limited English language proficiency. Websites must provide, for example, standardized information about QHPs to facilitate plan comparison, including premium and cost-sharing details, a consumer cost calculator, a summary of benefits and coverage for each product available, quality ratings, and provider directories. Marketplace websites also serve as an entry point for other insurance affordability programs, such as Medicaid, either by running a full eligibility determination or directing consumers to the appropriate state agency. The nature of health insurance enrollment also requires Marketplaces to collect sensitive personal information, and accordingly Marketplaces must meet federal privacy standards or face monetary penalties.

Many of the first Marketplace websites were a disaster, leading several to pivot to the FFM in their first year. Since then, both federal and state platforms have improved considerably and successfully enrolled millions of consumers. However, the ongoing maintenance and operation of these websites requires a considerable investment. Federal policy changes, such as the recent premium subsidy enhancements in ARPA and the Biden administration’s “family glitch” fix, can also require rapid and expensive updates to online eligibility systems. In both of those instances, some SBMs were not able to make the necessary changes to their websites in a timely fashion.

Marketplace Call Centers. SBMs are required to operate a toll-free call center to field questions and requests from consumers about the eligibility and enrollment process. Other than the requirement to have a toll-free call center, federal rules do not impose exacting standards on Marketplaces, such as staffing levels or maximum call wait times. Some Marketplace call centers have experienced system outages and significant wait times during their annual enrollment periods. Updated, clear federal standards and ongoing oversight of customer service quality could help avoid similar issues in the future.

Outreach and Enrollment Assistance. Federal regulations require SBMs to “conduct outreach and education activities . . . to educate consumers about the [Marketplace] and insurance affordability programs to encourage participation.” Other than being accessible for people with limited English proficiency and people with disabilities, SBMs have significant flexibility in how and to what extent they conduct this outreach.

SBMs are required to run and fund their own Navigator programs, although federal rules leave most of the details of those programs to the states. For instance, although all Marketplaces must establish certain training standards (such as training on meeting the needs of underserved populations), states can determine the content and frequency of those trainings.

Federal rules also do not establish a minimum funding level required for either Navigator programs or outreach campaigns. As a result, there is a wide range of SBM investment levels in these proven tactics for increasing coverage.

Process for Transitioning to a State-Based Marketplace

The process for transitioning to an SBM generally requires the state to submit two main components to the federal government: (1) a letter declaring the intent to transition, and (2) an “Exchange Blueprint” to demonstrate the state’s ability to operate a Marketplace. Federal regulators have made some adjustments to the Blueprint over the years, most notably allowing states to simply attest that they meet many of the federal requirements to operate a Marketplace instead of submitting documentation providing proof of compliance. And, despite stakeholder concern, beginning in 2024 Blueprint approval is no longer required at least 14 months prior to the start of the new SBM’s initial open period, allowing for a shorter timeframe between federal approval and an SBM becoming operational to serve consumers.

Setting a Bar: Potential Minimum Standards

Without additional minimum standards for the design and operation of an SBM, there is a risk that the consumer experience with the Marketplace will worsen, making enrollment more challenging and ultimately decreasing coverage rates. While the ACA clearly envisions a high degree of state autonomy over the operation of the Marketplaces, a few additional standards for SBMs could include, for example:

- A deliberative SBM transition process. Hiring staff with the necessary skills and expertise, procuring the necessary IT and other service providers, testing systems, building brand awareness, and engaging with assisters, carriers, and other stakeholders all take time. Given the stakes for consumers, it’s not a process that should be rushed. It could also be helpful for states to spend a minimum of one year as an SBM on the federal platform (SBM-FP) before fully transitioning to an SBM. This would provide some time for CMS to assess the state’s approach to governance, consumer outreach and assistance, and stakeholder engagement, before handing over full control.

- Transparency and community engagement. States should be soliciting and incorporating public comment on their proposed Blueprint, and publicly posting their Blueprint applications. Greater transparency surrounding SBMs’ revenue source(s) and spending, such as more prominent public posting of audits, as well as data on key metrics such as plan selections, effectuated enrollments, call center wait times, and spending on Navigators and consumer assistance is also critical.

- An investment in consumer outreach and assistance. Given the proven effectiveness of consumer outreach and assistance, it will be important for SBMs to meet minimum performance standards for consumer outreach, call center support, and Navigator programs.

- Standards for Marketplace health plans. Enrollees in all Marketplaces deserve to have plans that meet minimum criteria for certification. Although CMS has to date refrained from extending some standards, such as network adequacy, to insurers in SBM states, a federal floor could be helpful to avoid a wide divergence in consumer protections across states. At a minimum, if a state is not enforcing the ACA market reforms, it should not be operating an SBM.

Looking Ahead

To date, states have chosen to operate their own Marketplace based on a commitment to affordable, comprehensive health insurance for all their residents, with the SBM serving as a critical tool for achieving that goal. But in some states that may seek SBM status in the future, particularly those that have demonstrated antagonism towards the ACA’s coverage expansions and consumer protections, further federal guardrails could help reduce the risk of a decline in consumers’ experience and, in the worst-case scenario, a reversal of the recent gains in insurance coverage.

The authors thank Justin Giovannelli, Jason Levitis, Sarah Lueck, Claire Heyison and Tara Straw for their thoughtful review and editing of this post.

*Author’s note: This blog was updated on June 14, 2023, to correct an error in the list of state-based Marketplaces operating during the ACA’s first open enrollment period for plan year 2014, and associated errors in the timeline displaying when states shifted to the federal Marketplace platform or their own state-run platforms. Previously, the post erroneously listed 17 states as operating their own eligibility and enrollment platforms for plan year 2014, including two states—Idaho and New Mexico—that used HealthCare.gov for the first open enrollment period. Idaho transitioned to a state-run eligibility and enrollment platform for plan year 2015, and New Mexico transitioned to a state-run platform for plan year 2022. The exhibit and post have been updated to reflect these corrections.