By Katie Keith and Kevin W. Lucia. This blog originally appeared on The Commonwealth Fund Blog on April 5, 2013 and is reproduced here in its entirety.

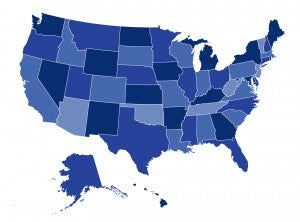

As of October 2012, only 11 states and the District of Columbia had moved forward to implement at least one of the Affordable Care Act’s 2014 private insurance market reforms. The other 39 states had not yet taken action, potentially limiting their ability to fully enforce the reforms. Without new legislation, regulators in at least 22 states reported that they would be limited in their ability to use all of the tools they need to protect consumers under the Affordable Care Act. These findings were reported in a recent analysis published in February and also presented in a webinar held in mid-March.

On March 15, 2013, federal regulators at the Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight released guidance on how the Affordable Care Act’s new market reforms will be enforced. This blog post describes the enforcement framework of the Affordable Care Act, how the new guidance fits into that framework, and what the new guidance means for enforcement of the law’s most significant reforms.

Who enforces the Affordable Care Act? States are the primary regulators of health insurance in the individual and small-group markets and can require insurance companies in their state to meet federal standards. If, however, a state fails to substantially enforce all or parts of the Affordable Care Act or notifies the federal government that the state does not have the authority to enforce it or is not enforcing the law, federal regulators at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) will step in to enforce. In doing so, federal regulators have the authority to assess significant fines of $100 a day for each individual that is affected by an insurer’s noncompliance.

What does the new guidance say? Consistent with an earlier analysis for The Commonwealth Fund that looked at the enforcement of the Affordable Care Act’s 2010 market reforms, the new guidance states that “the vast majority of states are enforcing the Affordable Care Act health insurance market reforms.” The guidance also recognizes that CMS has the responsibility for enforcing the reforms in states that lack the authority or ability to do so. In those states, insurers will be required to submit policy forms to CMS. According to the guidance, CMS will notify issuers of any concerns, conduct targeted market-conduct examinations, and respond to consumer inquiries and complaints. CMS will “work cooperatively with the state” to address any concerns about compliance and transition enforcement responsibilities back to the state when it is willing and able to assume enforcement authority.

States that are willing and able to perform regulatory functions but lack enforcement authority can enter into a collaborative arrangement with CMS, which would allow the state to enforce the Affordable Care Act using the same regulatory tools used to ensure compliance with state law. In addition, consumers would continue to contact the state with inquiries and complaints about their coverage. In the face of a potential violation of federal law, states would refer the issue to CMS for possible enforcement action if unable to obtain voluntary compliance from insurers.

As of March 1, 2013, four states—Oklahoma, Missouri, Texas, and Wyoming—had notified CMS that they do not have the authority to or are not otherwise enforcing the Affordable Care Act. An additional two states, Alabama and Arizona (for group PPO plans), made the same notification as of March 29, 2013.

What does it all mean? Federal regulators have recognized the need to ensure that there is adequate enforcement of the insurance market reforms that come into effect in 2014. The guidance offers a “middle ground” through the newly announced collaborative arrangements. These arrangements allow CMS to leverage the expertise of the states in monitoring their marketplaces and avoid dual regulation of insurers at the state and federal levels. This approach also may minimize consumers’ confusion and duplication of efforts by the states and CMS.

It is unclear, though, how the new arrangements align with existing federal regulations that require CMS to make a formal determination that a state has not substantially enforced federal law before stepping in to do so. Further clarification will be needed to address questions about: 1) whether CMS can bring an enforcement action against an insurer without first making a formal determination that the state is not substantially enforcing; and 2) whether federal law allows insurers to be subject to penalties at both the federal and state levels for the same violation.

Because questions remain about the coordination that might be required between state and federal regulators, states should consider whether new legislation or regulations—either to amend existing state law or give their insurance department more authority—are more appropriate to address enforcement gaps, continue meaningful regulatory oversight, and promote consumer protections at the state level. While the guidance shows that CMS is willing to work with and support states in their enforcement efforts, states continue to have the opportunity to enforce the new reforms and ensure that consumers receive the full protections of the law.