By Katie Keith, Kevin Lucia, and Christine Monahan. This blog originally appeared on The Commonwealth Fund Blog on July 1, 2013 and is reproduced here in its entirety.

This fall, under the Affordable Care Act, there will be new marketplaces in each state where insurance companies will sell private health plans. People without job-based affordable health benefits can go to these new marketplaces either in person, by phone, or on the Internet and choose a health plan. And many people will get help to pay for their plans. But recent polls suggest that many Americans remain unaware of these new places to buy health insurance or that they might be eligible for subsidies to pay for health plans. This means that consumer outreach and enrollment assistance in the marketplaces, also known as exchanges, will be vital to achieving one of the law’s core purposes: substantially reducing the number of people without health insurance in the United States. To help with outreach and enrollment, the law requires that every state marketplace establish a “navigator” program to support consumers.

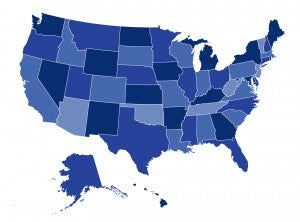

The Department of Health and Human Services recently released proposed rules that provide additional guidance on standards for the navigator programs, particularly for the 33 states that have decided to allow the federal government to operate their exchange. In these states, at least two different types of organizations must be selected to serve as navigators and federal grants must be used to fund navigator programs. Despite the federal government’s primary role in administering the navigator program in these states, many state legislatures have enacted or considered legislation that subjects navigators to state regulatory requirements.

This blog post describes the role of navigators and well as the potentially detrimental impact of this recent state legislative activity on effective consumer outreach.

What is a navigator? Under the Affordable Care Act, navigators must perform the following key functions:

- conduct public education activities;

- distribute fair and impartial information on health plan enrollment, premium tax credits, and free or low-cost coverage through Medicaid;

- facilitate enrollment in qualified health plans;

- provide referrals to other consumer assistance organizations or state agencies that address health insurance issues; and

- provide information in a culturally and linguistically appropriate manner.

Navigators may be self-employed individuals or organizations as diverse as trade, industry, and professional associations, chambers of commerce, and ranching and farming organizations. Each state must include at least one community and consumer-focused nonprofit group as a navigator.

The new navigator regulations recognize that states may choose to adopt their own navigator standards, but prohibit these state-specific standards from impeding application of the Affordable Care Act. For example, states cannot require navigators to be licensed as agents or brokers or to secure liability insurance against claims of wrongdoing such as errors and omissions insurance.

What’s the status of navigator requirements in states with federally facilitated exchanges? To date, 19 states with federally facilitated exchanges (including state-partnership exchanges) have enacted, or are currently considering, legislation that imposes state-specific requirements on navigators. Of these, 14—Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Maine, Montana, Nebraska, Ohio, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and Wisconsin—have already passed such legislation. (Utah—which adopted a bifurcated approach in which the federal government will operate the individual exchange and the state will operate the small-business exchange—also enacted navigator legislation.) An additional five states—Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania—are currently considering pending legislation or have sent such legislation to the governor to be signed.

Most of the bills require a navigator to obtain state licensure or approval before operating in the state. Many also establish training requirements, require criminal background checks, and authorize disciplinary measures against navigators. Some bills also subject navigators to existing insurance law (such as privacy and unfair trade practices standards) or require navigators to secure financial protection against wrongdoing.

What does it all mean? These state-specific requirements—which navigators will have to meet along with federal requirements—may lead to confusion and could limit navigators from performing their duties under the Affordable Care Act. Here are a few concerns that we have identified:

- Some requirements may prevent the application of the federal navigator program. A state law that prohibits navigators from offering advice about the benefits, terms, and features of a particular health benefit plan could prevent a navigator from facilitating enrollment and helping individuals make informed decisions, as required under federal law. For example, would state restrictions prohibit a navigator from “advising” a consumer with HIV about which plans cover certain antiretroviral drugs or “recommending” that a consumer consider plans that includes her providers in its network?

- Stringent standards could be a barrier for respected community-based organizations—such as agricultural extension centers, churches, and safety-net health care providers—that want to serve as navigators for underserved communities, including those whose primary language is not English, those who live in remote areas, and the uninsured.

- Many of these laws require the state’s insurance department to further define navigator requirements in regulations. Because many states have not yet issued regulations, potential navigators may be unable to comply with state requirements ahead of open enrollment in October 2013, potentially leaving a state without a navigator program.

As October 1 approaches, stakeholders are focused on the need to inform and educate millions of consumers who will be eligible for expanded coverage options. While all would agree that navigators must be held to high standards to ensure that consumers are protected, uncertainty remains regarding how state and federal regulators will interpret critical terms such as “advise” and “recommend.” This uncertainty could result in confusion and, potentially, litigation to determine whether state navigator requirements are preempted by federal law. To avoid confusion and delays or limits to implementation of effective navigator programs in each state, additional federal guidance on the scope of state-specific navigator requirements could be helpful as stakeholders prepare to help people get needed and affordable coverage.

3 Trackbacks and Pingbacks