On June 25, the House Committee on Energy and Commerce released the results of a year-long investigation into the practices of the Short-Term Limited Duration Insurance (STLDI) industry. The Committee looked into 14 companies that sell or assist consumers in enrolling in short-term plans. Its findings confirm what we have known for some time – short-term plans are a bad deal for consumers. Short-term plans are not required to comply with the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) consumer protections, meaning they can deny coverage to individuals with preexisting conditions, are not required to cover essential health benefits, and have major gaps and limitations in coverage that often expose consumers to significant out-of-pocket costs. The Trump Administration has made it easier to sell these policies by allowing short-term plans to be effective for up to 364 days, with the possibility of renewal. Oversight of the short-term market largely falls to states but, to date, only half have acted to limit their sales or to prevent short-term plan insurers from discriminating against applicants based on their health status. Even in states that have acted to regulate STLDI, their job can be difficult since the plans are often marketed deceptively and sold through complicated out-of-state arrangements. This has made it challenging for states to gain even basic information on what plans are being sold to their residents.

The Committee’s report corroborates these concerns and offers new evidence on the status of the STLDI market, including:

- Enrollment in short-term plans is increasing;

- Vulnerable consumers are ending up in short-term plans;

- Post-claims underwriting and plan rescissions are worse than we thought;

- Outright discrimination is rampant, especially against women; and

- Short-term plans aren’t sufficient even in the short term.

Enrollment in Short-Term Plans is Increasing

To date, little has been known about the size of the short-term market. In many states, once an insurer is approved to sell short-term policies they do not have to file for reapproval again, unlike ACA plans which undergo close annual scrutiny. A short-term plan approved in one state may then be sold in other states without having to gain regulatory approval, and some of the largest sellers of short-term products are not publicly traded insurers who would otherwise be required to report details on their membership. For these reasons and others, experts have not been able to secure enrollment data on the number of consumers enrolled in STLDI.

The Committee’s report found that, in 2019, approximately 3.0 million individuals were enrolled in STLDI across nine of the companies reviewed. Enrollment in these insurers’ short-term plans increased by 600,000 since 2018. While the Committee believes that it captured the largest sellers of STLDI in this count, it notes that the unregulated nature of these products and the lack of information on short-term sellers means enrollment in STLDI is likely even higher. By comparison, 11.4 million individuals enrolled in ACA plans during the 2019 open enrollment period, 3.0 million of which were consumers in state-based marketplace states. This means that the same number of consumers are enrolled in short-term plans as are enrolled in all of the state-based marketplaces.

What’s more troubling is that enrollment in short-term plans appears not driven by consumer demand, but by brokers’ sales tactics. The Committee found that enrollment in short-term plans increased between December 2018 and January 2019, with enrollments by brokers increasing 60 percent in December and 120 percent in January, compared to November enrollments. Even though short-term plans may be sold at any point during the year, these enrollment increases coincided with the open enrollment period for ACA products. During this time, brokers received “up to ten times the compensation rate” for selling STLDI compared to ACA plans.

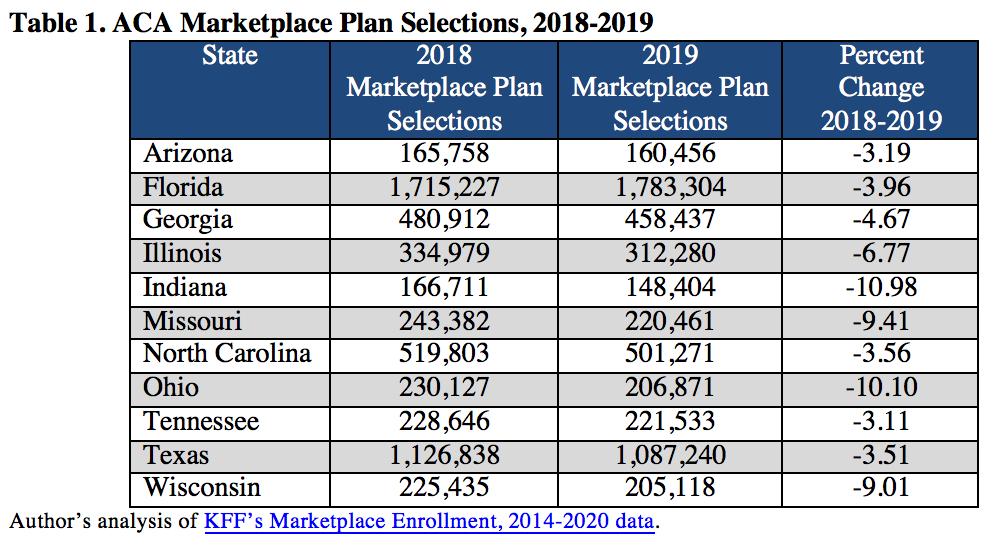

The marketing of short-term plans appears to have been deliberately designed to target consumers seeking ACA plans during the annual open enrollment season. The data suggest this strategy worked, significantly detracting from ACA enrollment. Indeed, of all the individuals enrolled in short-term plans, nearly one-third are consumers from Florida and Texas, with most of the remaining enrollment coming from nine states: Arizona, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, North Carolina, Ohio, Tennessee, and Wisconsin. As enrollment in short-term plans increased, ACA enrollments in each of these states declined (Table 1).

Vulnerable Consumers Are Ending Up in Short-Term Plans

Though short-term plans are not a good value for even the healthiest consumers, they are an especially bad option for consumers with ongoing or prior health conditions. Short-term plans have significant gaps in coverage and, generally, do not cover prescription drugs, mental health and substance use treatments, preventive care, and more. Many experts believed that insurers and brokers would steer people with preexisting conditions away from short-term plans, but the Committee investigation finds that this is not what is happening.

The Committee cites numerous instances of consumers who told brokers they had cancer, needed kidney surgery, had a history of asthma or heart disease, and who nevertheless were told that their preexisting condition would be covered and were enrolled in short-term plans. In other instances, the Committee found that consumers “specifically request[ed]” being enrolled in ACA-compliant plans only to be enrolled by brokers in short-term plans. These consumers were not attempting to hide or downplay their health status. Rather, they were forthcoming and were either misled or fraudulently enrolled in STLDI to their detriment. Once enrolled in short-term plans, these consumers were all denied coverage for treatment or their plans were rescinded.

Post-Claims Underwriting & Rescissions Are Worse Than We Thought

We’ve also known that short-term plans engage in aggressive post-claims underwriting practices, in which insurers comb through an individual’s medical file after they have already enrolled and received services to find a reason to deny payment for those services. This way, the insurer can collect an individual’s premium payments up until the consumer seeks care; then, they may deny coverage or rescind the policy altogether. While the ACA prohibited medical underwriting, these practices are commonly used by short-term plans.

The Committee’s report illustrates how easy it is for short-term plans to deny coverage for just about any reason. For example, in one case, a consumer was billed $280,000 after receiving treatment for an infection because his record included an earlier ultrasound that the insurer deemed “suspicious.” In other cases, consumers’ claims were denied even when their conditions were not previously diagnosed, they had not sought or needed treatment, and were not even aware of the condition. For instance, one insurer denied a consumer’s claims for cancer treatments because their condition would have caused “an ordinary prudent person to seek treatment” before enrollment, even though the insurer itself wrote that “no clinical documentation has been present that would establish your symptoms started between your date of coverage” and when the consumer ultimately sought care. Insurers also denied coverage when enrollees’ providers did not submit medical records within the requested time – in some cases, as short as 30 days.

Staying enrolled with the same insurer hasn’t seemed to help consumers. The investigation found that even consumers who first become ill after enrolling in a short-term plan are often later denied the opportunity to re-enroll. Essentially, once a consumer uses their short-term coverage, this use identifies them as someone with a health condition and insurers remove them from future membership.

Outright Discrimination is Rampant, Especially Against Women

Not only do these plans discriminate against individuals with preexisting conditions, but they are openly discriminatory against women. Many of these plans exclude coverage for basic preventive screening and testing services like pelvic exams and pap smears, even though these services are not expensive to cover. This technique is commonly known as “steering,” a practice in which insurers purposely do not cover a service to prevent those who need the service from enrolling. While discriminatory steering in ACA products is prohibited (and some early instances were quickly addressed), similar discrimination against women is permitted in short-term plans.

Many STLDI insurers reviewed also charge women more than men for the same coverage. One insurer currently charges women between the ages of 30 and 34 “up to twice the rate” of men. What’s more, all of the short-term plans require women to disclose whether they are pregnant, in the process of adoption, or undergoing infertility treatment. If a woman answers ‘yes’ to any category, she is denied coverage.

Short-Term Plans Aren’t Sufficient Even in the Short Term

Some have argued that despite short-term plans’ limitations and exclusions, they still offer value for consumers who might experience a catastrophic event. But, that isn’t the case. The Committee’s report reminds us again that short-term plans’ coverage of emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and intensive care unit services is severely limited. For example, one consumer’s trip to an ER left them with a $35,000 bill of which the short-term plan paid only $7,000. Another patient received a $14,000 bill for hospitalization for pneumonia and their short-term plan paid just $2,000. These plans impose low dollar limits even for necessary and life-threatening medical treatment.

Yet, these limits are not surprising given the Committee’s finding that, on average, “less than half of the premium dollars collected from consumers are spent on medical care by STLDI plans.” While ACA insurers are required to issue rebates to consumers if they do not spend at least 80 percent of premiums on medical care, short-term insurers are not held to the same standard. Today, short-term insurers are spending only 48 percent of premium dollars on providing care. This means consumers are paying a lot of money to get nothing in return.

Take-Away: The dangers of enrolling in a short-term plan have been well-documented, but the House Committee on Energy and Commerce’s investigation sheds new light on how this market is evolving. Enrollment in short-term plans is increasing, at least in part, due to broker incentives to steer consumers away from ACA plans, even if that is what consumer is looking for. Consumers with existing health conditions are ending up in short-term plans that leave them exposed and without insurance, and many short-term plans today are using any excuse they can to deny and rescind coverage. Short-term plans are openly discriminating against women and they do not protect consumers even in emergencies. Lastly, the most frequently used argument for the benefits of short-term plans – that they are affordable – doesn’t hold up in the face of data that enrollees are getting back only 48 cents for every dollar they spend in premiums.

1 Comment

If consumers who describe a history of heart disease are still enrolled over the phone in short term plans, this is blatant fraud by the broker. The broker is lying on the application.

If the short term insurer does not want to enroll pregnant women, or to charge more to women of child bearing age, this was considered acceptable insurance practice for many decades. Car insurance companies still charge much more to young male drivers, because they cause more claims.

3 Trackbacks and Pingbacks